Introduction

Following the so-called “44-Day War” in 2020, Azerbaijan and Armenia lodged reciprocal applications before the International Court of Justice (“ICJ”) under the UN Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (“CERD”), which is a part of the broader international claims between the conflicting parties.

These claims arise from Europe’s longest-running conflict that witnessed two destructive wars and decades-long military occupation and massive human rights violations. In its application, Azerbaijan accuses Armenia of practicing racial discrimination against ethnic Azerbaijanis through military occupation and ethnic cleansing of about a million of its citizens, cultural heritage erasure, and environmental aggression in the previously occupied territories. Armenia accuses Azerbaijan of racial discrimination during the so-called “44-Day War” and the post-war situation.

Azerbaijan’s broad-based claims raise critical legal questions on the relationship between military occupation and racial discrimination under CERD. In light of the ICJ’s recent disappointing judgment in the Ukraine v. Russia CERD case, the court now faces a Herculean task to assess Armenia’s three-decade-long military occupation policies and alleged human rights violations under CERD. In this author’s view, the court’s current framework is inadequate to assess transformative occupation and systemic human rights violations under CERD, which could leave millions of refugees without a proper remedy.

Background

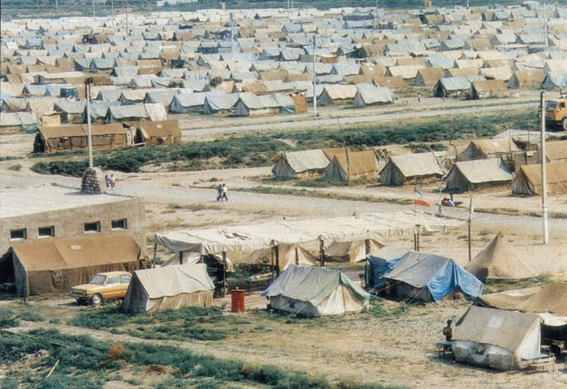

These inter-State claims arise from ‘Europe’s longest-running conflict’ that started in the early 1990s due to Armenia’s historical and territorial claims to Azerbaijan’s Mountainous Karabakh region, a province populated by a majority of ethnic Armenians. A devastating war in 1991-1994 resulted in Armenia’s military victory and the occupation of Karabakh and adjacent seven districts. The occupation displaced almost a million Azerbaijanis (“IDPs”) resulting in significant damage to their private property, civilian infrastructure, and cultural property. The UN estimated the total economic damage to Azerbaijan due to the occupation at $53.5 billion ($88 billion adjusted for inflation), a staggering sum for a small nation of Azerbaijan (see p. 52).

By relying on this extensive evidence, Azerbaijan accuses Armenia of committing acts of racial discrimination against Azerbaijanis in the formerly occupied territories and Armenia proper on the basis of ‘national and ethnic origin’ from 1987 to 2020. It attributes this ‘policy of ethnic cleansing’ to Armenia’s discrimination policy to achieve a mono-ethnic State (Azerbaijan’s application, see § 5-12). Unlike Azerbaijan’s extensive claims, Armenia’s claims are mainly dedicated to alleged CERD violations during the so-called “44-Day War” in late 2020 and the post-war situation (Armenia’s application, see §§ 6 & 7).

CERD Violations

Despite certain legal similarities, Azerbaijan and Armenia’s reciprocal ICJ applications are not equivalent. Azerbaijan’s application is not a response to Armenia’s claims, and it raises distinct claims under CERD, which has a broader scope of alleged violations and the historical period it covers. Azerbaijan raises four sets of claims against Armenia, namely, ethnic cleansing, cultural erasure, environmental aggression, and hate speech and disinformation.

A. Military Occupation and Ethnic Cleansing

Azerbaijan asserts that, between 1987 and 1994, Armenia unleashed a war to ethnically cleanse and annex a portion of Azerbaijan’s territory representing about 20 percent of Azerbaijan and populated predominantly by ethnic Azerbaijanis. In Azerbaijan’s telling, throughout that brutal war, Armenia continued its ethnic cleansing of about a million ethnic Azerbaijanis, expelling Azerbaijani civilians who resided in those territories and destroying Azerbaijani cities, towns, and cultural heritage (see §§ 7-12). This includes the massacre of over 600 Azerbaijani civilians in the town of Khojaly in 1992, which has been condemned internationally as an act of genocide (see § 10).

According to Azerbaijan, to implant and foster a new Armenian reality on the ground during its thirty-year occupation, Armenia’s ethnic cleansing campaign emptied the occupied territories of their Azerbaijani residents and actively encouraged ‘resettlement’ by ethnic Armenians (see §§ 13, 18-20). In this context, Azerbaijan alleges that Armenia violated CERD’s Articles 2 (not to engage in racial discrimination), 3 (prevent and eradicate racial discrimination and apartheid) and 5 (prohibit and eliminate all forms of discrimination).

B. Cultural Heritage Erasure

Azerbaijan’s second set of claims concerns Armenia’s alleged systematic wipe of Azerbaijan’s cultural heritage in the occupied territories. In Azerbaijan’s telling, Armenia simultaneously pursued an overarching policy of ‘cultural erasure’ in the occupied territories to remove any trace of Azerbaijani ethnicity or traditions by razing Azerbaijani districts and renaming others with Armenian labels, looting and destroying Azerbaijani cultural heritage sites (see § 11). Azerbaijan invokes CERD’s Articles 2, 5, and 3.

In the post-occupation phase, the emergent facts on the ground now reveal that the damage to Azerbaijan’s cultural heritage in the occupied territories has been immense and irreversible. According to well-documented reports, such cultural property erasure includes, mosques, churches, hundreds of historical and cultural monuments, libraries, cultural centres, music and art schools, museums, art galleries, theatres, ancient mausoleums, archaeological monuments, and archaeological sites. For instance, the Azerbaijani city of Agdam, and its famous Juma mosque, now better known as “Hiroshima of the Caucasus“, epitomises a massive cultural heritage erasure concerning tens of Azerbaijani towns and hundreds of villages that stand at the centre of this case. The scale of cultural damages in the occupied territories indicates the most extensive heritage erasure in modern history after the Second World War.

C. Environmental Aggression

Azerbaijan’s application also introduced a legal innovation in the form of “environmental aggression” as racial discrimination. It alleges that Armenia’s discriminatory policies denied essential resources to ethnic Azerbaijanis, as well as its exploitation of the natural resources and depredation of the environment in the occupied territories (see §§ 65-66). In Azerbaijan’s telling, Armenia denied Azerbaijanis access to “over 90 percent” of the Sarsang Water Reservoir, intentionally depriving Azerbaijanis who lived in territory controlled by Azerbaijan downstream of the reservoir of potable drinking water.

A novel aspect of Azerbaijan’s application is that it considers Armenia’s environmental destruction in the occupied territories as damage to its heritage under CERD. For instance, it asserts that Armenia’s environmental destruction has been threatened by the extinction of the Xarı Bülbül, Ophrys caucasica, a flower representing peace for the Azerbaijani people (see §§ 11 and 68).

D. Hate Speech and Propaganda

Azerbaijan also claims that Armenia has fomented and continues to foment ethnic hatred and racist propaganda against Azerbaijanis, including via its educational institutions, textbooks, and State media, traditional and social media. In Azerbaijan’s telling, this policy is conducted through a coordinated disinformation campaign and the dissemination of anti-Azerbaijani hate speech, calls to violence by hate groups like VoMA and other entities, glorifying individuals who have committed ethnically motivated crimes against Azerbaijanis. In this context, Azerbaijan invokes CERD’s Articles 2, 4, 5, and 7.

Conclusion: Towards the ‘Ethnic Enterprise’ Test?

When does military occupation become a practice of racial discrimination under CERD? The ICJ’s recent judgment in the Ukraine v. Russia CERD case disappointed many scholars and practitioners. The court rejected the vast majority of Ukraine’s claims related to Russia’s systemic military occupation policies, except for Russia’s school education policy in Ukraine’s occupied Crimea region (Judgment, para. 404). The case also revealed the court’s lack of a comprehensive legal test to assess the human rights dimensions of military occupation, which resulted in leaving millions of Ukrainian victims without an effective legal remedy.

The reality on the ground is that in modern warfare occupying States are engaged in what the International Red Cross calls a “transformative occupation” that aims at overhauling an occupied territory in line with their ethnic and national preferences. For instance, Russia’s publicly declared cultural erasure activities in Ukraine’s occupied Crimea, Donbas, Luhansk, and Kherson regions to ‘Russianize’ these territories have brought more international attention to transformative occupation. In this situation, military occupation is not aimed at controlling the territory for perceived security reasons but is a larger ethnic enterprise that aims at re-engineering the occupied territory ethnically or nationally. Distinguishing these two situations is essential for effective interpretation of CERD in occupied territories.

The longevity and massive nature of human rights violations in the previously Armenia-occupied territories call upon redefining CERD’s application in the context of military occupation. In this author’s view, to have an effective legal interpretation, the court should go beyond its narrow legal framework of assessing particular occupation policies and assess military occupation as a whole. In this respect, the proposed ‘ethnic enterprise’ test can provide a “missing link” in interpreting military occupation as racial discrimination as a whole under CERD.

First, the ICJ should assess whether a particular military occupation is of a transformative nature. This requires assessing whether the occupying State aims at obtaining an overarching ethnic and national policy goal in its totality, e.g., achieving a mono-ethnic State in the occupied territories. This will allow the court to determine the ethnic policy intentions of an occupying State or its ideological underpinning triggering the application of CERD.

Second, if the test’s first prong is in the affirmative e.g., military occupation is found to be an ethnic enterprise, then particular policies should be interpreted as being subordinate to this overarching goal. In this respect, in the Ukraine v. Russia case the ICJ erred in taking a narrow view of Russia’s occupation by focusing on specific elements (e.g., educational policy) without evaluating it in light of Russia’s overall occupation as a whole.

In the author’s view, this two-prong ethnic enterprise test would equip the ICJ to evaluate military occupation not only as a breach of public international law but also as a practice of racial discrimination in its totality and have an effective legal interpretation to achieve the object and purpose of CERD.

Nurlan Mustafayev, is a counsel on international legal affairs and instructor on public international law at Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy. Views expressed in this blog post are personal and do not represent those of his employer or any governmental institution.