Background

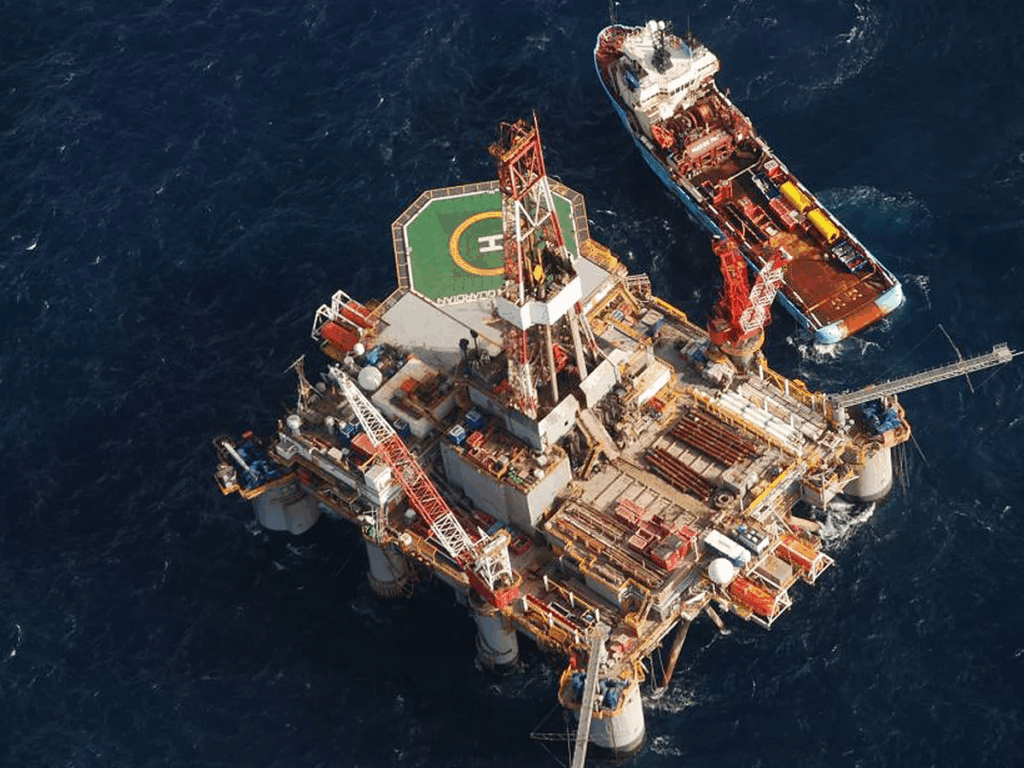

In December 2015, the Italian government enacted Law No. 208/2015, banning offshore hydrocarbon production within 12 nautical miles of its coastline, citing environmental and safety concerns. This legislative measure directly impacted Rockhopper Exploration plc (‘Rockhopper’), a UK-based energy company holding concessions in the Ombrina Mare oil field in the Adriatic Sea. Rockhopper initiated arbitration proceedings against the Italian Republic (‘Italy’) under the Energy Charter Treaty (‘ECT’) before the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (‘ICSID’).

Rockhopper alleged that the legislative ban amounted to a breach of Italy’s obligations under the ECT. It advanced two central claims: first, that the measure constituted an unlawful expropriation under Article 13 of the ECT, which requires that any expropriation be accompanied by prompt, adequate, and effective compensation; and second, that Italy violated Article 10(1) of the ECT, which guarantees fair and equitable treatment (‘FET’) standards for foreign investors.

This analysis examines two interrelated issues raised by the proceedings: the tribunal’s exercise of judicial restraint in deciding the case solely on expropriation grounds, and the procedural irregularities in the tribunal’s constitution that led to the award’s annulment. The annulment of the award by an ICSID ad hoc Committee (‘Committee’) on 2 June 2025 highlighted the structural relationship between substantive adjudication and procedural legitimacy in ICSID arbitration.

The Tribunal’s Initial Award

In the award rendered in Rockhopper Exploration plc v. Italian Republic (‘Rockhopper’), ICSID Case No. ARB/17/14, the tribunal disclaimed any intent to engage in judicial law-making. It stated that it had ‘sought to assiduously refrain from any form of ‘legislating’ and trusted ‘that the Award will be read in that spirit’ (Rockhopper, para 11). This framing signaled a conscious effort to limit the award’s scope to the facts and treaty provisions strictly necessary to resolve the dispute.

Yet the tribunal’s methodological restraint was marked not by a narrow interpretation of individual treaty provisions, but by its decision to resolve the dispute exclusively on expropriation grounds under Article 13 of the ECT. It concluded that Italy’s measure amounted to direct expropriation lacking prompt compensation (Rockhopper, para 197). Italy argued that the measure constituted a lawful exercise of its sovereign regulatory authority and relied on the police powers doctrine, which permits non-compensable regulation enacted in the public interest. The tribunal rejected this argument, finding that the denial of the production concession did not fall within the scope of such regulatory authority. It held that Italy’s actions failed to satisfy the cumulative requirements for lawful expropriation under Article 13 of the ECT, including the obligation to provide prompt, adequate, and effective compensation.

In addition to the expropriation claim, the investor submitted a separate claim under Article 10(1) of the ECT, alleging that Italy had breached its obligation to accord FET to foreign investors. The claim centered on the frustration of legitimate expectations and lack of transparency in the regulatory process. Although both parties had addressed the standard, the tribunal declined to decide the issue, holding that its expropriation finding was sufficient to dispose of the dispute (Rockhopper, paras 200-203).

The Annulment

The Committee annulled the Rockhopper award (‘Rockhopper Annulment Decision’) on 2 June 2025 on the ground of improper tribunal constitution under Article 52(1)(d) of the ICSID Convention (‘Convention’), which allows annulment for a ‘serious departure from a fundamental rule of procedure’. The basis for annulment was the failure of arbitrator Dr. Philippe Poncet to disclose circumstances that could give rise to justifiable doubts as to his impartiality.

Although the Convention does not define what qualifies as a fundamental rule of procedure, ICSID annulment jurisprudence has consistently treated impartial tribunal constitution as falling within this category. In Eiser Infrastructure Limited v. Spain (‘Eiser’), ICSID Case No. ARB/13/36, the annulment committee held that an arbitrator’s failure to disclose connections with a party’s expert violated Article 52(1)(d) of the Convention. Similarly, in Caratube v. Kazakhstan (‘Caratube’), ICSID Case No. ARB/08/12, nondisclosure of professional ties warranted annulment.

While no actual bias was alleged or proven, the Committee in Rockhopper found that nondisclosure alone sufficed to undermine confidence in the tribunal’s impartiality (Rockhopper Annulment Decision, paras 373-374). Relying on the approach adopted in Eiser,the Committee reiterated that procedural legitimacy under the ICSID framework depends not merely on actual impartiality, but also on the appearance of impartiality as perceived by a reasonable third party. The Committee emphasized that ‘the possibility cannot be excluded…that the Award might have been different had the Tribunal been properly constituted without Dr. Poncet as a member’ (Rockhopper Annulment Decision, para 405). That possibility, without requiring proof of actual impact, was determinative.

Although annulment committees are limited to reviewing procedural compliance under Article 52 of the ICSID, their reasoning may articulate concerns that indirectly touch upon a tribunal’s legal reasoning or the perceived balance of its conclusions, particularly where issues of impartiality or appearance of bias arise. In such cases, findings on the improper constitution of the tribunal may implicitly raise concerns about how interpretive discretion was exercised. In this sense, the decision reinforces the idea that procedural safeguards are not ancillary but constitutive of arbitral legitimacy.

Critical Reflections: Procedural Boundaries and Substantive Gaps

The Rockhopper Annulment Decision illustrates that procedural rules are not mere formalities but fundamental constraints on the exercise of arbitral authority. While investor-state tribunals enjoy interpretive discretion in applying treaty standards, this discretion is institutionally contingent on transparency, impartiality, and compliance with procedural norms.

The nondisclosure by arbitrator Dr. Poncet casts a shadow over the award’s reasoning. As the Committee emphasized, even in absence of finding substantial bias, the appearance of partiality alone can comprise the legitimacy of investor-state arbitration (Rockhopper Annulment Decision, para 406). This reflects a consistent line with ICSID’s jurisprudence in Eiser and Caratube, where tribunal constitution failures led to annulment irrespective of the outcome.

Yet the procedural deficiency also had substantive consequences, insofar as it left untested a key claim advanced by the investor. Despite submissions concerning transparency, regulatory change, and legitimate expectations, the tribunal’s refusal to engage with the FET claim under Article 10(1) of the ECT left unresolved the evaluative standards that often contextualize expropriation findings. The tribunal effectively excluded regulatory rationale from legal analysis and magnified the legal consequences of its expropriation finding in isolation.

This contrasts with earlier ECT-based awards under ICSID jurisprudence. In Vattenfall v. Germany, ICSID Case No. ARB/12/12, the tribunal found expropriation but dismissed the FET claim. In RWE Innogy v. Spain, ICSID Case No. ARB/14/34, and Antin Infrastructure Services v. Kingdom of Spain, ICSID Case No. ARB/13/31, the tribunals found FET breaches grounded in regulatory inconsistency and frustrated expectations, while rejecting expropriation claims. Yet even where tribunals engage substantively with both standards, procedural integrity remains decisive. In NextEra Energy v. Spain, ICSID Case No. ARB/14/11, the award was annulled on procedural grounds, demonstrating the primacy of tribunal impartiality and procedural compliance. These cases demonstrate that FET standards and expropriation are analytically distinct but often applied in parallel. FET addresses the predictability and fairness of state conduct, while expropriation is focused on economic deprivation. Their combined application enables tribunals to weigh investor protections against state regulatory autonomy more comprehensively.

The Rockhopper tribunal’s doctrinal engagement created a substantive lacuna. The analytical omission of foreclosing a more integrated inquiry assumes significance in light of the procedural defect that ultimately led to annulment. The Committee’s suggestion that the award ‘might have been different’ implicitly recognizes that an improperly constituted tribunal may exercise legal judgment in ways that affect substantive outcomes. From this point of view, procedural irregularity carries implications for the persuasiveness of interpretive reasoning itself. (Rockhopper Annulment Decision, para 405).

In this sense, Rockhopper is a cautionary tale about the limits of judicial restraint when procedural integrity is compromised. The annulment mechanisms under Article 52 of the Convention thereby serve a dual role: they enforce procedural accountability and, indirectly, discipline tribunals’ interpretive discretion. In doing so, it reminds both tribunals and practitioners that legitimacy in investor-state arbitration arises as much from process as from substance.

Conclusion

The Rockhopper annulment underscores that procedural integrity is not a peripheral concern in investor-state arbitration. The tribunal’s decision to limit its analysis to expropriation, while framed as judicial restraint, left the scope and content of the FET standard unresolved. That partiality of engagement became more problematic in light of the tribunal’s improper constitution, which ultimately rendered the whole award vulnerable to annulment.

The Committee’s decision reaffirmed that the legitimacy of an award depends not only on its reasoning but also on the tribunal’s adherence to institutional standards, particularly those regarding impartiality and independence. Its reasoning reflects a broader institutional principle: where procedural failings threaten confidence in a tribunal’s integrity, annulment may be warranted even absent proof of actual bias.

This case does not merely illustrate a failure of disclosure; it exemplifies how procedural enforcement may operate as a structural constraint on arbitral authority. In the contexts where tribunals navigate tensions between investor protections and sovereign regulatory space, procedural discipline functions as an indirect check on interpretive discretion.

More broadly, Rockhopper resonates with contemporary debates about the future of investment arbitration. As the ECT faces scrutiny in cases like Klesch v. Germany and Komstroy v. Moldova, this annulment reflects a shift in emphasis: from expanding treaty interpretations to consolidating institutional credibility. In this landscape, procedural boundaries are not only the guards of fairness, but also the vehicles through which the balance between investor rights and state sovereignty is increasingly recalibrated.

Tommaso Giorgio Maria Moneta is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Innsbruck, specializing in public international law.